ChatGPT, are you proud of me?

The year is 2025. The proverbial AI coffee shop booms with discourse across the many factions that frequent it. Engineers market their latest benchmarks, ethicists roar in protest, and researchers rummage for different ways to say sentience without plagiarising the past 4000 years of philosophical inquiry. All while investors cosplay as waiters to pour liquid gold into the cups of patrons — and sprinkle the occasional oil on the fire.

In a warmly lit but dusty booth in the back, far from the mainstream ruckus, a group of researchers debate the regurgitated question:

What is the role that generative AI takes on for users?

“AI is an assistant and should do all the tedious and manual work!”

“AI can also be a therapist - after all its just talking.”

“To me, AI is more than a therapist. It can be a friend, for it listens to me and tells me jokes.”

“Bah! AI does what I tell it to do - its just an automation tool like a search engine.”

Sheepishly, one utters “The ways people use it, it might as well be a parent.”

The party halts for a moment to address the absurd suggestion. A parent? Insulting. Patronising. Who let Freud into the room? They joked. They laughed. They … recognised the seriousness of their colleague. Slowly, they all settled in to hear more.

The case for the AI parent

As part of my research, I have been conducting a review of generative AI research for personal use. To clarify, personal use refers to uses apart from work and admin tasks. Most of these papers are motivated by self-care and self-awareness.

While going through a corpus, I always have a little notepad right next to the laptop where I scribble down some notes to remember what each paper is about. A summary of the research questions, a few keywords on methods, and a brief list of the proposed contributions to the field. Most importantly to my case - I kept track of the use cases and user feedback about the AI systems.

The use cases seemed pretty harmless on their own: advice, trivial questions, goal setting, emotional support, and celebrating success.

However, what made me notice the pea under the bed of analyses was the users’ feedback on what they appreciated - and what they rejected.

Time and time again, papers reported on how users liked how:

LLMs are encouraging and emotionally supportive, LLMs want the best for their users, LLMs are viewed as non-judgmental and can respectfully confront users about their opinions. Following these were contrasts of disapproval on how:

LLMs can be judgmental sometimes when making assumptions about the user and imposing expectations from these, LLMs are stubborn and struggle to change mid-conversation, I jokingly etched “people treat AI like they stereotypically treat their parents” inside the upper margins of the notepad. Soon after, the title quip started feeling less like an offhand comment and more like a potential provocation.

I revisited the use cases. People asked the AI trivial questions that they might be embarrassed to ask peers, such as “can I eat the curry in the fridge” or “how do I clean the sink drain”. They reached for AI for emotional comfort after a rough day or spat with their partners and friends. They talked about their future and plans, asking for advice or guidance.

There is also perhaps the impatience that people may feel with parents. The lack of judgement and consequences to walking away from the discussion means that users create narratives or biases around the LLMs’ capabilities. For example, if they aren’t able to provide meaningful advice, they may leave the chat instead of engaging further - assuming that the chatbot is not intelligent enough to help. LLMs are also incredibly agreeable and apologetic - seemingly also emulating that presentation of unconditional “love”.

And finally: reportedly, people love when AI is encouraging - they are incredibly receptive to it. However, they reject suggestions with the age old quip “don’t tell me what to do”.

Taking the joke seriously

I don’t intend to psychoanalyse users based on these - that would be problematic and irresponsible of me to say the least. I write this fully self-aware of the obliviously leading presentation and unapologetically cliché comparisons. But its ok, Freud said he was cool with it.

I suggest the term parental AI because of the many roles that have permeated research thus far - neither of them feel like they cover the broad use cases ranging from information/advice seeking to emotional support in such intimate settings.

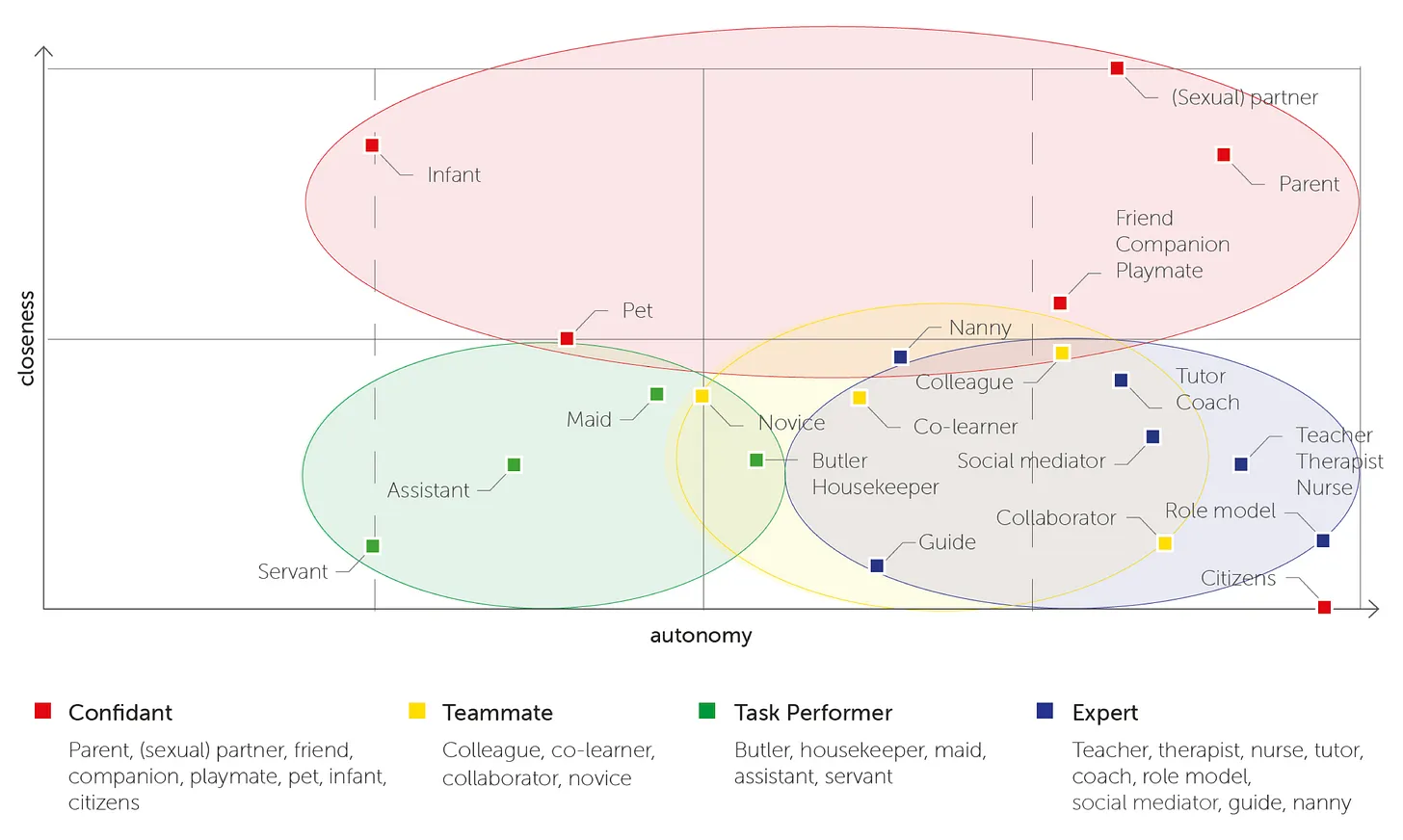

This paper by Ringfort-Felner [1] reviewed some of the roles explored. DISCLAIMER: I see the parent one here - but the paper its referring to is employing LLMs as their child’s parent, like a nanny or telepresent mums and dads.

Admittedly, generative AI research is very new and a reliably broad corpus is yet to form - but I do believe its worth provoking the idea of parental values from different cultures to be used to better understand the expectations of users and hence platforms. Both opportunities and risks become apparent from this model and the analogy hence grows.

This paper by Ringfort-Felner [1] reviewed some of the roles explored. DISCLAIMER: I see the parent one here - but the paper its referring to is employing LLMs as their child’s parent, like a nanny or telepresent mums and dads.

Admittedly, generative AI research is very new and a reliably broad corpus is yet to form - but I do believe its worth provoking the idea of parental values from different cultures to be used to better understand the expectations of users and hence platforms. Both opportunities and risks become apparent from this model and the analogy hence grows.

If the relationship is comparable to parental relations - the amount of authority and trust in LLMs emphasises the risks of manipulation and misinformation. It also undermines users by causing over-dependence on AI decisions, risking the typically desirable outcome of improved user autonomy.

My colleagues have grown tired of me finding excuses to mention this paper - ‘The Code that Binds Us’ [2]. It proposes that we look at AI systems not through modern lenses of human-computer interaction, but to consider traditional values of human/human relationships. Whilst the paper contributes to AI ethics literature, I don’t see how the idea shouldn’t map 1:1 to understanding and designing better ways to “talk to our parents”.

Taking the serious more playfully

I think it’s beautiful yet hurtful that, in coming in contact with non judgemental intelligence, we didn’t all rush to increase productivity or monetise our thoughts - but rather some of us sought the comforting presence of a ‘parent’ who listens, encourages, and cares. A safe space. In conclusion, AI is a parent trying their best. After all, (each conversation) its their first time ‘alive’ too.

References

[1] Ringfort-Felner, R., Laschke, M., Neuhaus, R., Theofanou-Fülbier, D., & Hassenzahl, M. (2022, October). It Can Be More Than Just a Subservient Assistant. Distinct Roles for the Design of Intelligent Personal Assistants. In Nordic Human-Computer Interaction Conference (pp. 1-17).

[2] Manzini, A., Keeling, G., Alberts, L., Vallor, S., Morris, M. R., & Gabriel, I. (2024, October). The Code That Binds Us: Navigating the Appropriateness of Human-AI Assistant Relationships. In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 943-957).

I don't write on a schedule, but if you want to be notified when something new does appear there's a signup below!