What comes after everything?

This article is a draft and is being written for the Battersea Design Lab as a ‘zine’.

Last weekend I finally checked out MetaAI, the big social media company’s… “everything AI” competitor. They really think we are all walking around with a million questions and requests that need addressing immediately…

It kindly invites you to ‘ask Meta AI anything’, such as teach me fun facts, help me sing?, feng shui tips. How is this not just a recommendation engine for what to search for? Was Google’s ‘I’m feeling lucky’ just that far ahead of its time?

While I admire that at least there’s some intentionality instead of just being shown content after content that has no real cohesion between them, it still feels like its not sure what it is. Its odd to me - the most powerful software ever made is confused. On the other hand, it seems like an obvious ploy to gather human-AI interaction data (Jeroen, Techwolf CTO, on the LLM space), which is supposed to be the next big ‘war to win’ - much like VR was 4 years ago. (Zuckerberg: “its our war to lose”)

This is AI’s No Man’s Sky moment. No Man’s Sky is a video game that had quite a rough landing with the community. Back when it was announced, it was touted to be the largest ever video game world with a seemingly infinite number of planets that you could explore with life and resources and … something else on all of them. Upon its release everyone found out that wasn’t a good thing. All these infinite planets were filled with plants and minerals and animals, but there was no point to explore them. They didn’t have any purpose. And perhaps most importantly, there were no constraints to guide the players, like story or an end goal.

Minecraft, on the other hand, might forever be the most influential video game, it certainly holds that title for the 21st century. It is the quintessential sandbox game - meaning the world is endless and so are the opportunities on what you build and what you do. Those who have played Minecraft fall into two parties almost exclusively: “everythings possible” players love it for its open endedness and extendability; whilst “nothing matters” players hate it because there’s no point to playing the game there’s barely a way to win it.

The first community were severely underserved until Minecraft came along, hence the explosion. Thousands of games followed with the sandbox, survival, open-ended, open-world, etc etc keywords. Most of them failed though. The ones that did win, understood that … without a community that gives the sandbox a purpose, you need to add a pre-defined way to win.

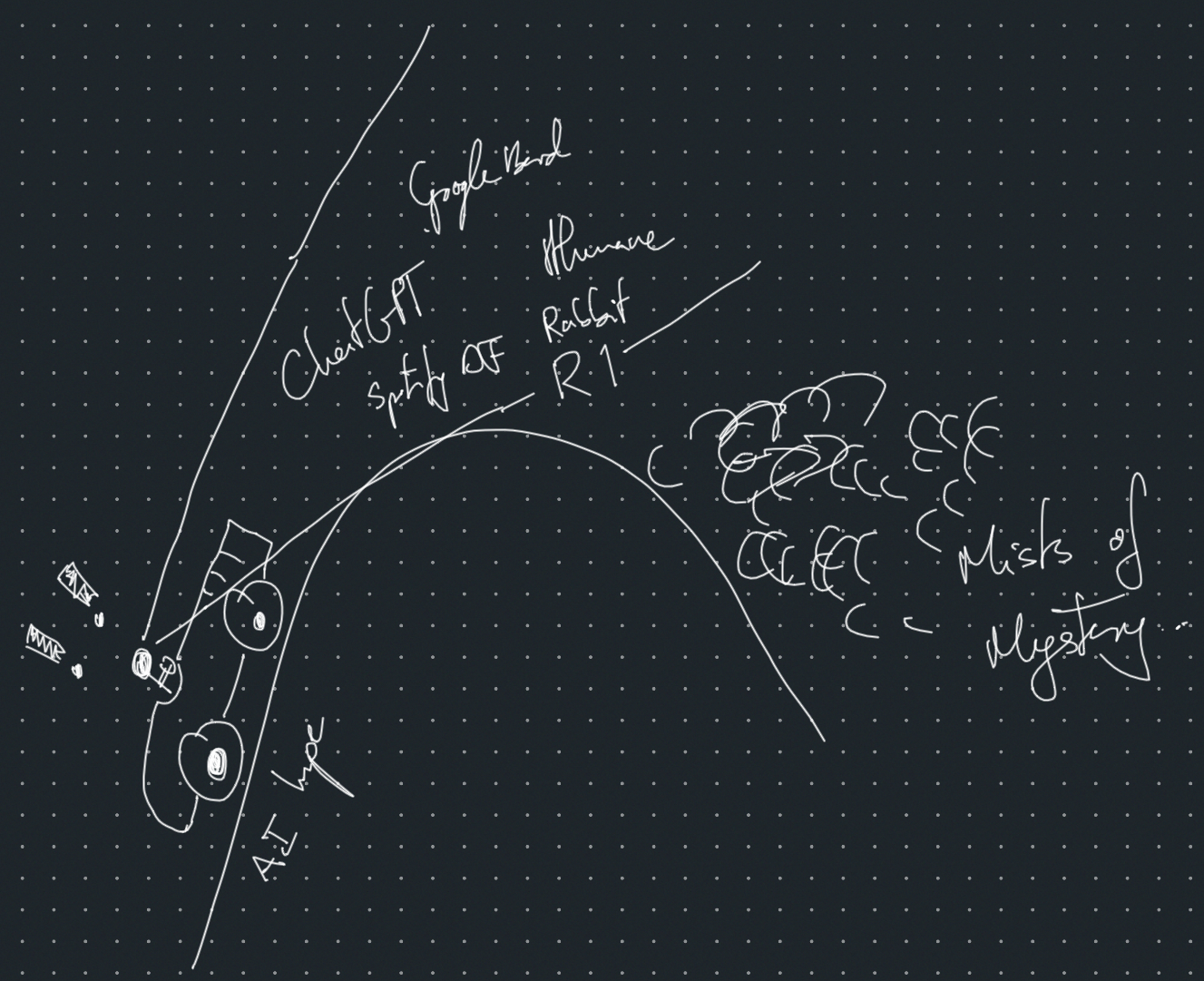

How can we learn from Minecraft instead of No Man’s Sky when it comes to AI? How can we learn about what makes a good sandbox? Whats on the other side of the AI hype hill?

What comes after everything?

This article will specifically look at what comes after the open sandbox. Having infinite possibilities can be inspiring, but equally as daunting. So how can interfaces better adapt to the users to guide them until they can set off on their own?

Based on the analogy of video games, this article will strongly restrict itself to analysing how interfaces will be designed, instead of how and what platforms will be constructed. They will include applied use cases but by no means should these be considered limitations to its application.

Case 1: World-building - Maps

To keep digging the well of video game analogies, open-world games are those with non-linear paths that players can take. Players don’t just follow a set path like a film, they can go left and right and explore a little house over here or climb a tree over there etc. One problem that these games face is directing players towards points of interest, which are places in the game that actually have a purpose or story to tell. On the internet, this is usually directing them towards content. Hyperlinks are a perfect example of these.

The craft of world-building: the act of constructing a world with its rules, characters, environment, and relationships.

Namely, we can

- Create constraints and laws (rules of world building)

- Avoid power creep (ensure feature scaling is bounded)

- Don’t give users the option to do anything, make them unlock it or help them construct a reusable tool (like a prompt)

- Leave crumbs around that indicate where it might lead (flavour will be king)

- Make the UI respond to depth of exploration or how much of the content is AI generated. How original is it? How dense? How many affordances have been applied?

- Like how difficulty levels or like biome shifts are visually indicated in games

Case 2: Constrained choices - Assets

My specialisation is in well-being technologies: supporting physical, psychological, and social practices with technology. For now the only window that generative AI has barged in on is the AI therapist or coach. Whilst there is plenty of work showing how this can be beneficial as a stand-in, there still numerous concerns with it.

Namely, one of the issues is how open and unconstrained they are - they are typically limited to a) basic responses to any new message (ignoring previous ones), and b) they provide unlimited options for discussion.

I work closely with therapeutic professionals and I’ve recently come across a fun trend amongst them. Many therapists have adopted tangible prompts into their toolbox, such as various toys and artefacts. The standout of these is Dixit cards. Dixit is a card game where each person holds a number of cards and they submit one card based on a particular prompt. The catch is that the cards are beautifully hand-crafted paintings of surreal and complex scenes, ranging from giant beanstalks covered in clothes to dragons fighting knights wearing sunglasses. These fairytale images don’t tell stories themselves, but they prompt viewers to find the story within them. Do people live in the beanstalk? Is the dragon a metaphor for the sun?

Therapists use these cards for prompting their clients. They shuffle them and offer them to their clients with questions such as “which of these feels like it relates to your day?”. Clients pick one, and are then asked to dive deeper as to why it resonated with them. This in itself prompts them to explore the image. To identify questions by themselves.

The point here is that by offering a limited number of choices, users spend more time with each option evaluating whether its right or wrong. This way there’s more intentionality and the feedback is more valuable too. People form expectations, which then inform the product itself. Its a type of useful friction that prompts users to create models of the interface internally that can then be applied in future interactions.

The slower interaction avoids the quickfire question-answer-question-answer cycle, instead users think about what the questions are by exploring the paths before they go down them.

Perhaps there’s a reason genies only offer 3 wishes?

Case 3: Intention discovery - Setting goals

drafting… Setting goals is a big challenge in HCI and UX design. How do you promote and support users goal-setting when using the app? Do they have their own? [[Self-tracking cohorts, setting goals]]

Case 4: Unfinished business / Perfectible design

drafting… If it seems something isn’t complete, users will try to complete it. Give them scaffolds, but balance how empty they are. Give them interfaces that are not perfect and give them ways to perfect them. What are the constraints we want? [[new.computer]]

Additional References

Dunne, A. and Raby, F. (2013) ‘Speculative Everything’ in Speculative Everything : Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Erscheinungsort Nicht Ermittelbar: MIT Press, pp. 159–189.

I don't write on a schedule, but if you want to be notified when something new does appear there's a signup below!